Lindsey Gray – 22.8.2016

Down in a quiet corner of your garden or local park, there might be an extraordinary IUCN Red List threatened species and important evolutionary “missing link” waiting for you to come and meet it.

Looking like a five year old’s rendering of a caterpillar brought to life, these charismatic little creatures wait out the heat of the day burrowed in moist leaf litter, rotting logs, or squeezed into the tiniest of soil crevices.

These creatures are Onychophorans, or velvet-worms, and they provide some stiff competition to our other friends in the cutest invertebrate category. They are basically fuzzy-worms with chubby tentacle legs (“parapodia”) and furry antennae – like a cross between a Muppet and a centipede. They have beautiful velvety skin (hence the name) that depending on the species can take on some extraordinary Persian-carpet like geometric patterns.

Onychophorans, or velvet worms, have beautifully textured though extremely thin skin. Don’t leave them out in the sun.

They are also super squishy, with their only really hard body parts being little grasping hooks on the end of their fat legs. They cope with the lack of hard exo- or endo-skeleton by moving through using a hydrostatic skeleton. Hydrostatic skeletons are cool. Imagine that instead of our hard bone skeleton, we had a series of tough, fluid filled tubes embedded in our muscle system instead. Imagine that all these tubes were connected together, a bit like a framework built from interconnected water-bombs. When the muscles in one part of body contracted, it would force the liquid to another location where are muscles are relaxed. Just like squeezing one end of a long water-bomb and watching all the water move to and bulge at one end. I can’t imagine how we would get about with this human-hydrostatic skeleton (we’d probably slosh around all over the place – see you later facial features), but thankfully velvet worms can expertly manage their own.

You should definitely check out some videos of velvet worms crawling. They move extremely slowly, gliding along a rhythmic wave of legs on either side of their body. By the way, they can also walk backwards. Impressive.

(http://www.shutterstock.com/video/clip-14805973-stock-footage-costa-rica-a-velvet-worm-slowly-crawls-along-a-mossy-branch.html)

A handsome Onychophoran

The beautiful skin of velvet worms is apparently only one micrometre thick! Even the finest human hair is a whopping 40 micrometres wide. Their thin-skin is also very stretchy and porous. So while being squishy and stretchy is good for things like absorbing soil water and for squeezing into tiny soil spaces, it does mean velvet worms dry out rather quickly when exposed to dry air. Next time you find one (which hopefully you will), following the obligatory examination and iphone photo-shoot, return it to its soily home ASAP.

Other cute but ruthless predators! Sugar gliders eat swift parrot chicks (above) and tarsiers… ruthless (below).

A hungry velvet worm holds nothing back. They have earned a special place for themselves alongside swift-parrot munching sugar-gliders and live-lizard eating tarsiers. Animals whose super-cute and adorable appearance belies the uncomfortable fact that they are actually terrifying, hardened predators.

Velvet worms have two huge slime glands on either side of their mouths that eject high-pressure streams of slimy, enzyme rich saliva that encases their unwitting snail, termite or worm prey in a sticky net. This slime not only stiffens up, preventing prey escapees, it also kicks off the process of prey digestion extra-orally. Similar to what happens in spiders, by coating the prey tissue in enzyme rich saliva, velvet worms save on chewing (remember no hard parts) and simply sup up the pre-prepared nutritious broth. Lucky we are big hey? Most velvet worms are only a few centimetres long, so we are fortunately outside their target prey range.

A velvet worm dousing its prey in sticky, digestive enzyme laden slime.

You should definitely try and meet a velvet worm. Have a fossick under logs, in the soil and amongst the leaf-litter. They are not common though – you will have to be dedicated in your quest. One reason why so many velvet worms are considered endangered is because they are so rare (more on that in Velvet Worms. Part II). Here at the Haswell Museum, we only have microscope slide velvet worm specimens. These slides are of velvet worm body cross-sections. The slides are very old and are used in teaching Zoology students comparative invertebrate anatomy.

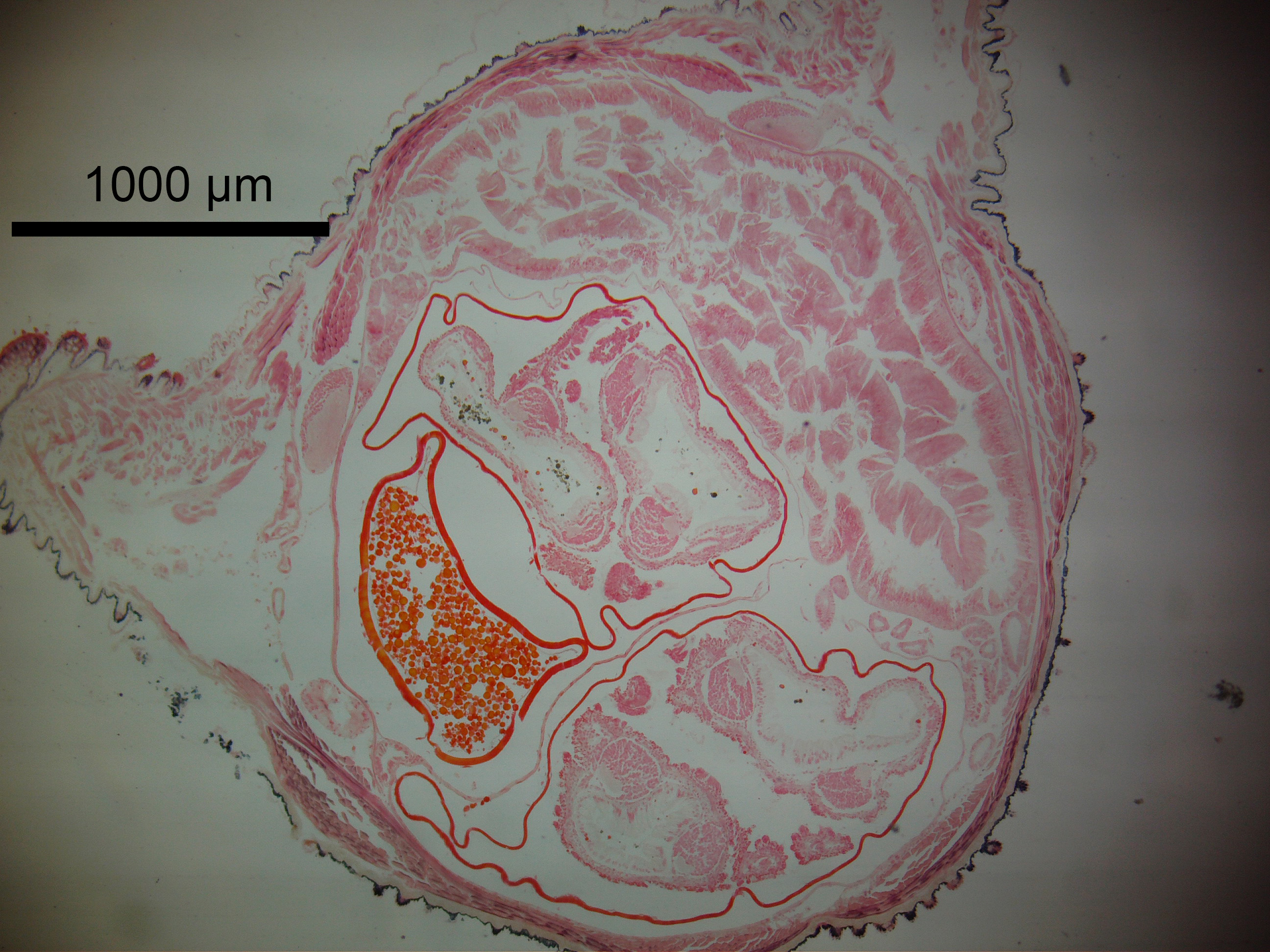

A micrograph by volunteer Joe Ibrahim of a velvet worm in cross-section showing its internal organs. Its legs (parapodia) can be seen sitting at the top left and right hand sides of the section.

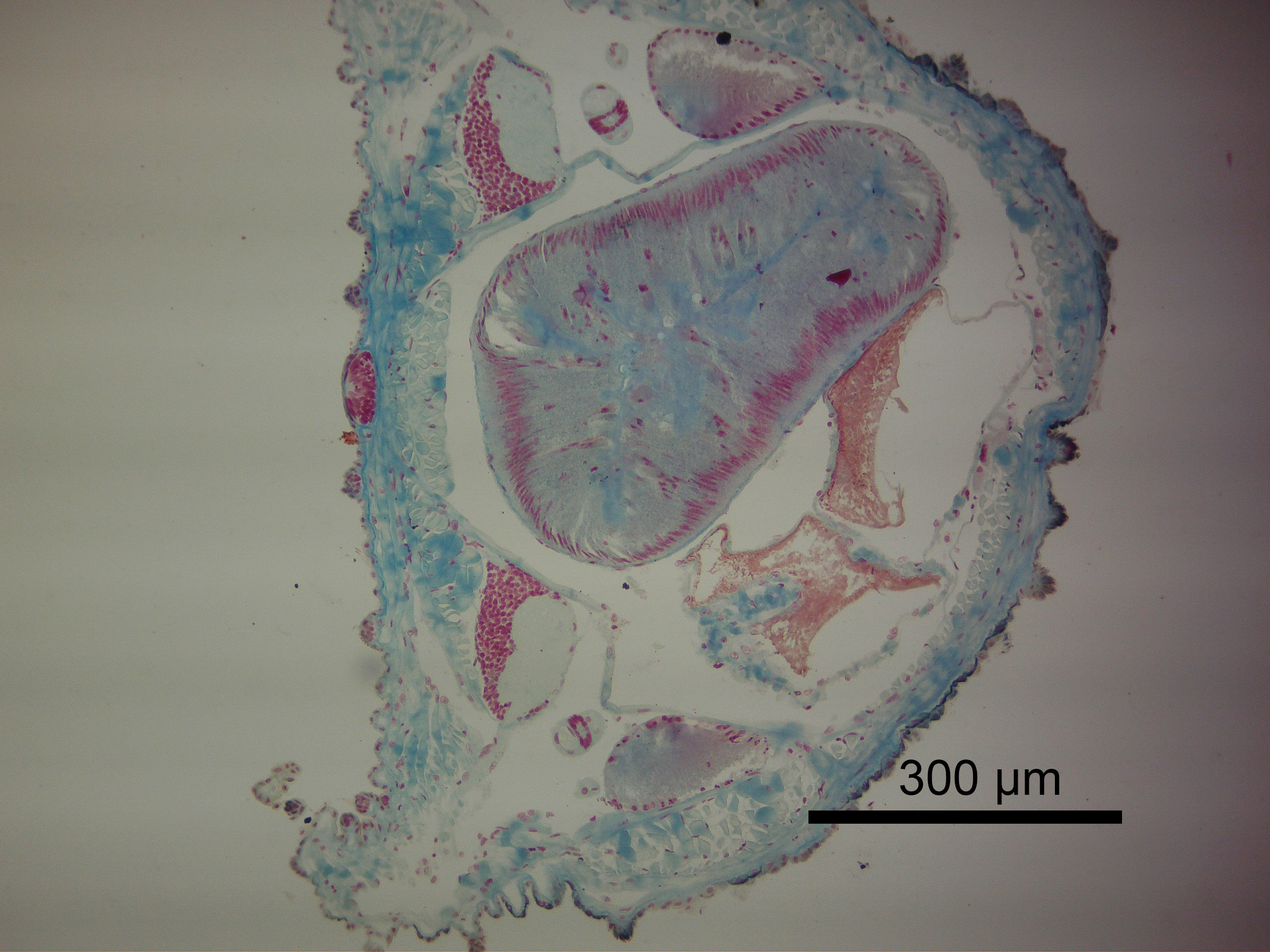

Another micrograph by Joe. This one is also a transverse section (cross section) and shows many of the organs drawn in the diagram below, including the slime or salivary glands. See if you can spot them (source: http://lanwebs.lander.edu/faculty/rsfox/invertebrates/peripatus.html).

We were so astonished at how amazing velvet worms are that we could not fit all of the amazing details about them in a single post. Please come back soon for a second Onychophoran instalment to learn about their unusual mating behaviours, where in the world they live and why they are so important to students studying evolution.